There's a heat alert in Greece: temperatures are soaring and the government has advised citizens to leave their homes as little as possible. In the refugee camp of Moria2, on the island of Lesbos, it is very hot. In the extensive area of tents and containers, huddled together just a stone's throw from the sea, the sun isn't letting off: the trees can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

The number of refugees on the island has decreased this year, but the desperation has increased: every day it seems more difficult to obtain permits to reach the destination of one's long and often dramatic journey.

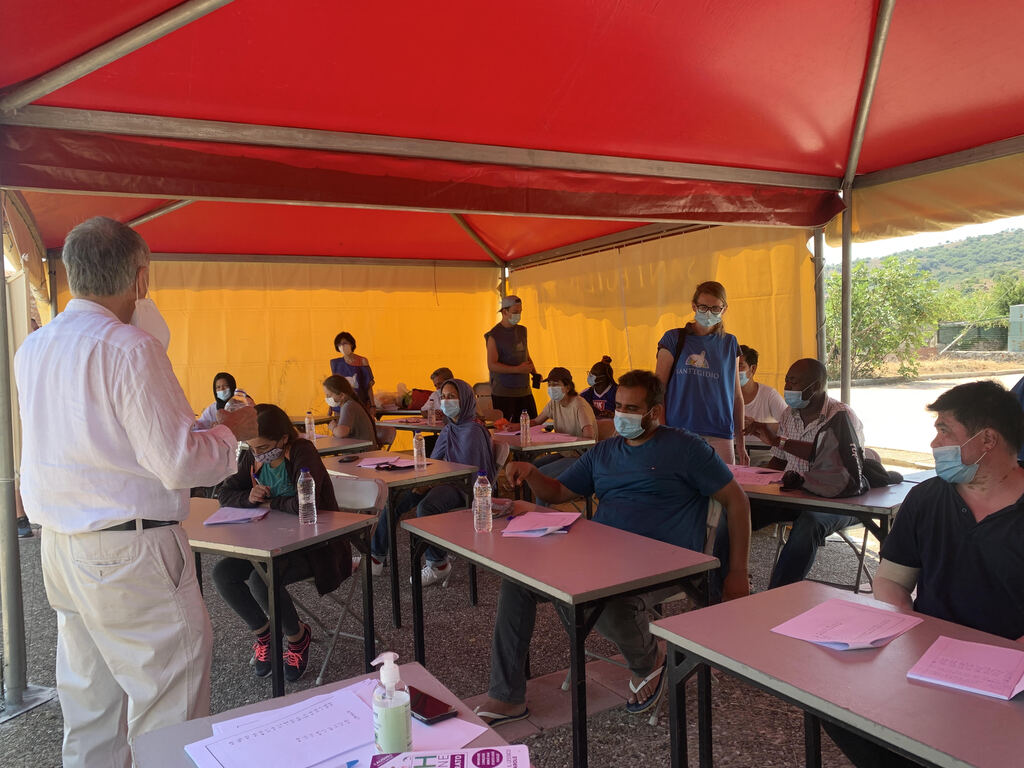

The red domes of the "friendship tent" are next to the camp, a little higher up: there are shady tables where children come in the mornings for the School of Peace and in the afternoons they can eat there with their family, then stop to chat and play checkers or backgammon, while the children run around in a wide, safe space. A little further on, the tents of the English School, in the same bright red, with desks, blackboards, a teacher and many "assistants" who help those who, now adults, have had little education, but bring a lot of hope and a desire to learn with them.

These days there are almost 90 "volunteers" (there will be more than 250 throughout the summer), mostly young people, from various European countries: from Portugal to Poland, via Spain, the Netherlands, Italy, Belgium, Hungary and Germany. They came at their own expense, to spend their holidays with the refugees on the island. They are joined by some Greek friends and young migrants who facilitate the friendship by translating into Arabic or Farsi. It is the enthusiasm of gratuitousness, which infects many and which - beyond the language and cultural barriers - is the message of Sant'Egidio to the refugees, the "added value" of the red tents, where, with food, education, some medical advice, one breathes the fresh air of friendship.

Today's videos