Fifteen years have passed since the murder of Floribert Bwana Chui in Goma. His corpse was found on 8 July 2007. He was atrociously tortured and killed: the manner suggests that his murder was meant to be a warning to others who could follow his example.

What was his fault? Floribert was a young member of the Community of Sant’Egidio. He was a customs officer of the Office Congolais de Contrôle (Occ), the Congolese agency that checks the quality of the goods which go through Congo. In his capacity of ‘claim agent’ in Goma, some month before he had to impound and destroy shipments of damaged foodstuffs, rise in particular. He revealed that he had been offered bribes in order to let damaged foodstuff pass. The consumption of that food would have been dangerous for the people and so he refused. Such refusal to succumb to corruption was the reason of his death.

Pope Francis once said: «Corruption demeans the dignity of the person and shatters all the good and great ideals. The entire society is called to commit to countering the cancer of corruption, which, with the illusion of fast and easy incomes, actually impoverish all». Accordingly, Floribert gave up an easy money to remain faithful to the Gospel which he knew, shared, and lived with his brothers of the Community of Sant’Egidio in Goma, and with the street kids of the School of Peace.

He confided to a nun, a friend of his, that, as a Christian, he could not accept to put the health of many people at risk. «Do I live in Christ or not? Do I live for Christ or not? That is why I can’t accept. It’s better to die rather than accept a bribe», he said.

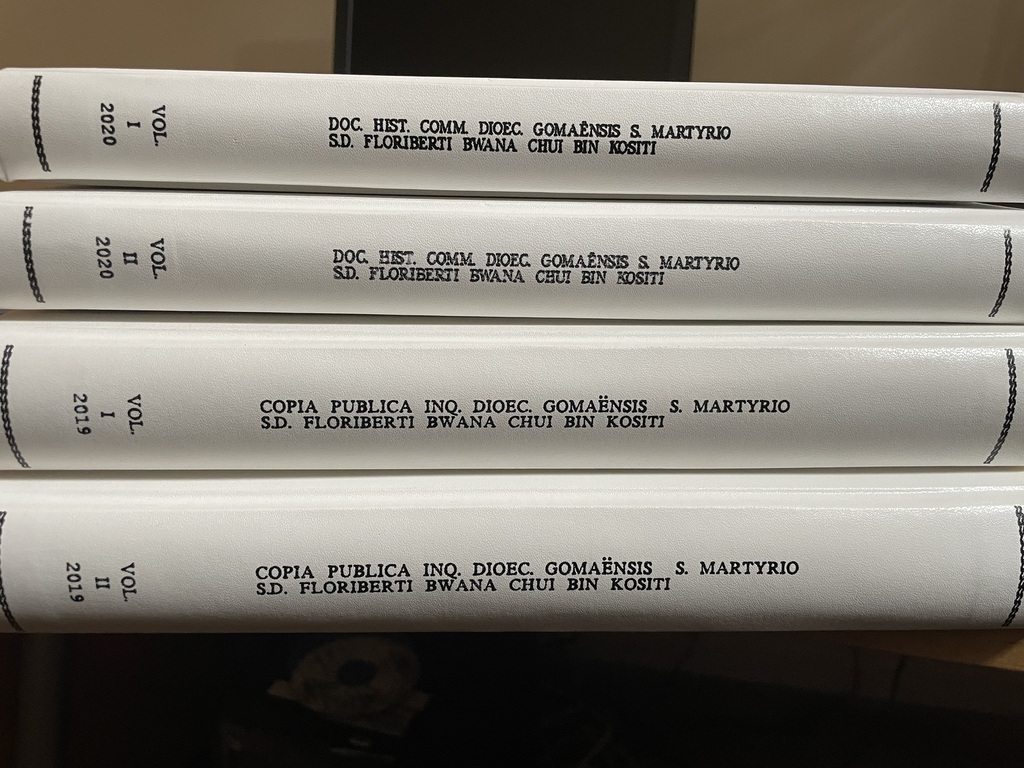

In these very days the Community of Goma celebrate the 15th anniversary of Floribert’s death. He was proclaimed Servant of God at the end of the diocesan phase of the beatification process, opened in March 2015. The Congregation for the Causes of Saints issued the decree of legal validity of the Acts and in the meantime proceeded to publish them on 8 April 2022. It is an important step in the proceeding which should recognize the martyrdom of this brother of ours.

Floribert’s choice to oppose that attempt at corruption was the fruit of a life deep-rooted in the Gospel, lived close to the poor and the children. So, Floribert is already proposed as a paragon of moral integrity: it is not a case that nowadays in Goma if someone does not accept to be corrupted, or behave honestly on the border, is called ‘a Bwana Chui’.

Pope Francis has often raised the topic of corruption as a global issue for economy and politics, especially in the developing countries: it is sufficient to recall that, out of the twenty countries most affected by corruption ranked in the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index, ten are African and all of them are involved in conflicts. In such context, while in eastern Congo there are still tensions among different ethnic groups and the borderline of Goma – where economic and commercial interests and regional conflicts intertwine – is a battlefield once again, Floribert’s figure is a witness to a Christian peaceful reaction to that global plague.

He has been proclaimed ‘Servant of God’ already: the Cause of Beatification is underway.

.jpg)